Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve mentioned that I’ve been learning React JS. First in the article “Reaction to React JS and Associated Bits” and then last week in my article “Test Driven Learning”.

In the first article, I mentioned that if you use React JS, you’ll probably end up using the Flux design pattern and since there are multiple ways of implementing flux, getting a clear definition of what it is and how it should work can be confusing. At least, I found it confusing.

And now that I’ve figured it out, I thought it might be helpful both to myself and to the programming community at large if I offered my own Explanation of the Flux Pattern. At the very least, it will give me one more way of solidifying the concept in my own brain. Maybe it will be helpful to you as well.

Flux “One Way Data Binding”

One of the first concepts you’ll hear when you start to learn Flux is that Flux implements “One Way Data Binding.” This is unfortunate because if you start implementing Flux thinking it is any kind of data binding, you are already headed in the wrong direction. Data binding holds with it this concept that things will happen automatically and declaratively. Neither is true in the Flux world. In fact, the reason Flux exist at all is because, in the Flux world, control over what happens when is the reason for its existence. So, forget data binding. Flux is “One Way Data Flow”.

Pub/Sub

Flux is heavily reliant on the pub/sub model. Pub/sub is short for Publish/Subscribe. This comes from the real world. You subscribe to a newspaper, or magazine, or… whatever. Every time the thing you subscribe to is published, you get it.

It is no different in Flux. An object will subscribe to another object. Anytime the second object does something worth publishing, the first object gets notified.

The beauty of implementing a system in this way is that the publisher doesn’t need to know anything about the subscribers. If there is a subscriber, the subscriber gets notified. If there is no subscriber, nothing happens. The subscriber does need to know something about the publisher so that he can say he wants to know when something is happening. While you might thing this would create a tight coupling between the two, it doesn’t have to.

Singletons

There is a pattern in object oriented programming called “Singletons.” Just like the name implies, this means there is only one object of that type in the system. Some people consider Singletons evil. But the benefit, especially in the Flux world, is that finding an instance of the object is easy. You just ask for it.

Flux Dispatcher

The Dispatcher is the central Flux object. If you are using the Flux implementation from Facebook, your Dispatcher object will extend the Dispatcher class. There really isn’t much too it, and you may be able to get away with just using the Dispatcher class directly. But I create a new derived object so I can extend it if I need to.

Everything in the system that needs to know when something interesting happens in the view layer of your code, subscribes to the dispatcher. And anytime something happens in the view layer that other objects in your system might want to know about, the dispatcher is called with a message telling it what action we are looking to perform.

So, in the demo app I am building, when the main view loads, the componentWillMount() method in my view sends the dispatcher a message telling it that it is looking for a list to display.

1 | componentWillMount(){ |

On the other end of this request, I have a store that has registered with the dispatcher.

1 | AppDispatcher.register((action) => { |

You’ll notice that I am using “enumerations” to keep the code clean. The reality is the ActionTypes are just strings.

Flux EventEmitter

We have notifications flowing down to our store to tell it we need some information or want it to do something, like save the data. But once that is complete, how do we let the view know that the information it needs to display has changed? Well, it is actually very similar. The view tells the store, “Hey, any time you do something interesting with the data, let me know.

So, once again we setup a Pub/Sub relationship. This time, the store is the publisher and the view is the listener. So, in our view, we’ll setup the listener by adding it to our componentWillMount() method

1 | componentWillMount(){ |

I’m using superAgent here to make an ajax call that will get me the list. When it returns, I call emitChange which will eventually call the callback I passed in from the view to tell the view that something changed.

Push vs Pull

Now, there seems to be two minds about how this all should work. Do you just notify the view that something happened and let the view go get the data it needs? Or do you pass the data the view will need along with the notification? It would seem to me that while either one will work, if we think of Flux as “One Way” data flow, or even One Way data binding, it makes a lot more sense to push the data around. And so, what you’ll see me do in the callbacks that live in my view code, is that they will receive the data and push it into the view state.

1 | onChange(type,data){ |

Visually

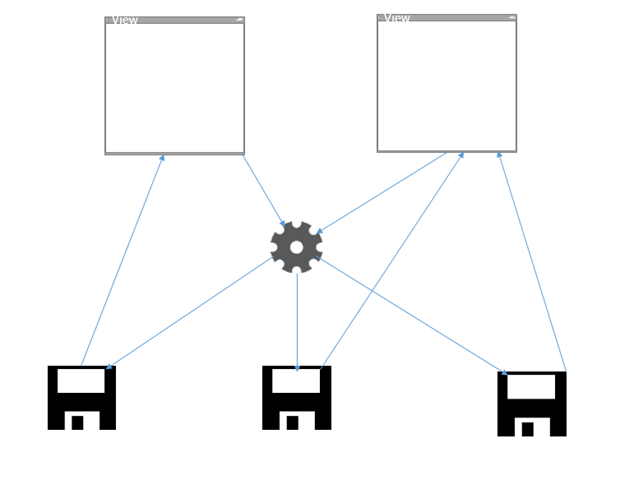

The arrows represent the direction of data flow. You can assume that if the data is flowing to something, there was a corresponding listener setup.

The arrows represent the direction of data flow. You can assume that if the data is flowing to something, there was a corresponding listener setup.

The top windows represent the view. The cog represents the dispatcher (you can see that it sends the notification to everything) and the disks represent the data stores. You should note that the dispatcher notifies all of the stores because there is only one dispatcher to listen to. Finally, since not all of the views care about all of the stores, I send notifications to particular views that care.

There may be cases where you would have something at the store level that isn’t, technically, a store. That’s OK. But I think 99% of the time, you’ll end up having stores be thing thing that the dispatchers send information to.

Conclusion

I have not given a lot of implementation details here because what I wanted to convey was the overarching concept behind Flux. Once I’ve finished my reference app for this, I may go into more detail at the implementation level. Don’t forget to sign up for the newsletter so you don’t miss anything.