If you are using one of the many frameworks that say they are using JavaScript MVVM, you might not be using it the way it should be used. Many of my clients aren’t.

This article will attempt to answer three questions.

- What is MVVM?

- What are the advantages of MVVM?

- What are good MVVM coding practices?

What is JavaScript MVVM?

The first question we need to ask before we can ever start coding is, “What is MVVM?” The reason for this is that if you don’t understand what this design pattern is attempting to do, you’ll probably ending up making some pretty severe coding mistakes when it comes time to implement it.

In the MVVM design pattern, like the MVC design pattern, the first M represents the Model and the first V represents the View. As with MVC, the Model represents the data you are trying to manipulate. The View represents the presentation layer. In MVVM, there is also an entity called a ViewModel which is an object or set of objects that represent the View’s State. This would include any data you want to present from your Model as well as ancillary states such as what elements are enabled/disabled or visible/hidden. Not that these are the only items. This is just a few examples.

What makes MVVM cool is that you don’t have to worry about how data gets from the View to the ViewModel or from the ViewModel back into the View. That all happens automatically. Although, depending on the implementation, you might have to write a bit more code to notify the View that something changed in the ViewModel so that it knows to update itself.

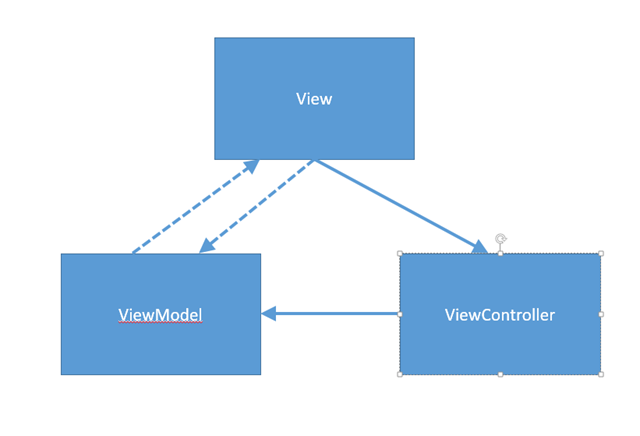

But, you may be left wondering, “Where do event handlers go?” Well, that is one of the things I find confusing about calling it MVVM. Because in every implementation I’ve ever worked on, there is still a controller of some sorts. Or, call it a ViewController. It is the thing that responds to events in the view and updates the ViewModel as needed.

So, in general, you have a View that updates the ViewModel automatically and fires events to the ViewController. This is all specified declaratively. When an event is fired, the ViewController responds to the event and updates the ViewModel with any state changes. When the ViewModel changes, it notifies the View that the View should update the presentation. When the controller needs to know about the current state of the View, it ask the ViewModel for that information because it should be reflected there.

If you’ve ever used one of the many MVVM frameworks out there, you’ll recognize that many of them combine the ViewModel and the ViewController into one entity. I’ve separated them out here for clarity and because I believe that if all possible, they should be maintained separately to maintain the Single Responsibility Principle. However, I recognize that the best you may be able to do is provide to separate sections in one class. The main point here is that any state changes to the view happen because the ViewModel was updated and not because the ViewController called into the View to make the change.

If you’ve ever used one of the many MVVM frameworks out there, you’ll recognize that many of them combine the ViewModel and the ViewController into one entity. I’ve separated them out here for clarity and because I believe that if all possible, they should be maintained separately to maintain the Single Responsibility Principle. However, I recognize that the best you may be able to do is provide to separate sections in one class. The main point here is that any state changes to the view happen because the ViewModel was updated and not because the ViewController called into the View to make the change.

What JavaScript MVVM is Not

One rookie mistake with any MV* design pattern is that many programmers think that the View, ViewModel or ViewController are the only three places where code can live in this pattern. But the truth of the matter is, the pattern only describes how to handle the organization of your presentation code. MVVM does not specify where your business rules should be located. But one place they should not go is in your ViewController. The only code that should be in your ViewController is code that updates or retrieves information from the ViewModel, or code that calls out to another class to perform some sort of business rules.

Advantages of JavaScript MVVM

While there are many advantages to using MVVM, the top three on my list are:

View Refactoring

I’ve worked on several systems in the past where it was necessary for my code to know what more about the View that it should have. Whenever I wanted to change the ID of an element in my view, it was necessary for me to update code in other parts of my system or the code would break. When you are using MVVM properly, you can not only change your view however you want, but you don’t have to even have an ID if you don’t need to for some other reason (like running Selenium Tests).

Interchangeable

In fact, if you wanted to, you could create multiple views and associate each of them with the same ViewModel and ViewController. You might create a View for a version of you application that runs on the desktop and another View for a version that runs on a phone. Implemented correctly, you may have state information in your ViewModel that never makes it to the View because the version of the View you are currently running doesn’t display that information.

Testing

For me, the most compelling reason to us MVVM is because it makes it much easier to test my application. You only need to be able to tell the ViewController where the ViewModel is. You can call the event handlers directly in your test and verify that they update the ViewModel correctly without ever having to create a View. Since the View is declarative, you can trust that your framework will do what it should and leave testing the View to a larger Application level test rather than trying to unit test it.

JavaScript MVVM Best Practices

Never Call the View from the ViewController

There are several ways I typically see this rule violated. The first, and most obvious is when the view is called to retrieve or set state information instead of using the ViewModel. But another way I typically see this violated is when programmers insist or writing event wire-up code in the ViewController. The reason wiring up event handlers is a bad idea is because now I have to have some sort of DOM locator code in my ViewController. This means if I change the identifier or the location of the DOM item, I have to come in and change my locator code. One way of testing if the code you are writing belongs where you are writing it is to ask the question, “If I executed this code without the View, would it still work correctly?”

Event Handlers Should Be Light

As I mentioned above, you don’t want to have any more code in your ViewController than is absolutely necessary to update the ViewModel. This will often mean calling out to some other object to get the actual work done.

ViewModel Should Only Contain ViewState

It might be tempting to put executable code in your ViewModel at times. Resist this urge. If you need a computed property, that’s one thing. If you start processing business logic, you are probably headed down the wrong path. My general test here is this. If I need to write a test case against my ViewModel code directly to get 100% code coverage, I’ve probably coded something wrong. Of course, you have to be writing unit test and a code coverage tool for this rule to work.

If You Think You Need to Violate A Best Practice

Finally, I want to address the issue of, “What if…” This past week, I ran into a situation where the control I was using was not setup to implement MVVM the way my framework intended. So, this problem is fresh in my mind. The solution is almost always to extend the component and add in the hooks you need so that you can use the framework properly. While the temptation to just get something working will be strong, your overall productivity will suffer if you start bending the rules. If you can’t figure out how to get the code to submit, ask for help. You may need to break some of the rules in the extension, but at least the violations are isolated from the rest of your code in such a way that if the component ever gets fixed, you can go to one location to update your code.