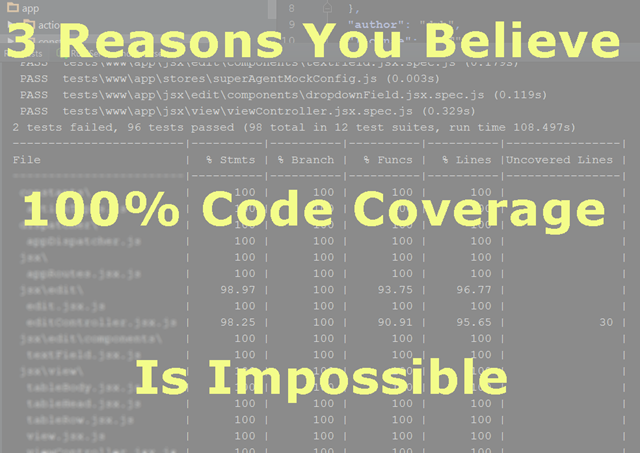

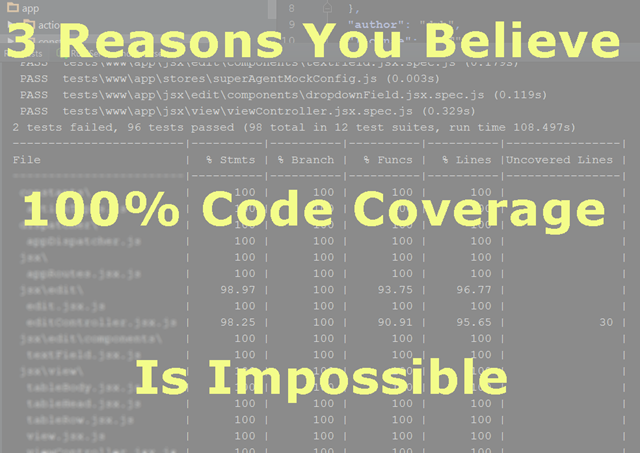

I’ve written about Test Driven Development before. I’ve even written about 100% code coverage before. And I haven’t written much about it recently because I’ve been focused on JavaScript. But, I’ve been thinking about the 100% code coverage debate more and I have a few more thoughts on the subject.

You see, the more I practice Test Driven Development, the more inclined I am to believe that there are only three reasons for arguing against 100% code coverage.

There is Something Wrong with Your Framework

This will be the easiest one for most people to accept. It isn’t so personal.

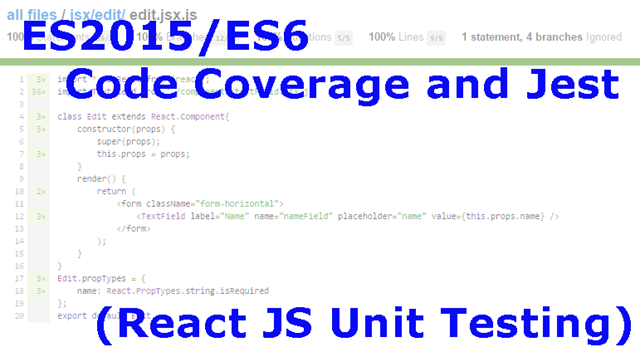

You see, I’ve been learning React JS and, as I’ve mentioned before, I decided to learn React AND learn to test it at the same time. The thing that has impressed me from the outset is that ALL the code that I write is testable. Where a lot of other frameworks are testable except for the View, React JS is ALL testable.

And this got me to thinking, if all the code you write is testable, why wouldn’t you write tests? In fact, as I wrote in “Test Driven Learning, an Experiment”, the process of writing the tests as I go has helped me understand React JS better than if I had not.

But compare this to other frameworks where the View is basically HTML. There is no really easy way to write tests for HTML. At least, none that I know about.

And then there are frameworks that seem to do all they can to make it hard to test. When I was using Ext JS 4.x, I spent two years looking for a way to make my code testable without having to have the View rendered because the way they had implemented “MVC” made loading the view mandatory. Talk about tight coupling! Fortunately, now that they’ve implemented MVVM, if you do this correctly, it solves these problems.

Another place where I found testing difficult was with Angular 1. Most of Angular 1 is quite testable. It was created with testing in mind. But as I was trying to add a decorator to the UI Grid component, I found that testing the decorator was quite difficult. This, I believe, said more about how the UI Grid component had been created than about how the Angular framework was put together. But this just illustrates my point. Sometimes, the reason you can’t test has more to do with the tools you are using than any other reason.

Then again, the problem may be you.

There is Something Wrong with Your Code

Now, arguably, in my last example, the reason I was not able to test the decorator for my Grid was because I was missing some fundamental concept related to testing decorators in general or how that related to the Grid.

The reason I say this is because the one thing I’ve noticed the more I test is this. The more I practice TDD, the easier TDD becomes.

As I introduce testing into the organizations I work with and as I’ve grown in my own TDD skills, the one thing I’ve noticed is that when we start out learning TDD, it almost always starts out as DDT. That is, Development Driven Testing.

This is, of course, better than not testing at all, but if you wait until after you’ve written your code, or you develop your code without thinking about how you will test it, you will almost always end up in a situation where you will have to rearrange your code to make it testable. Untestable code is probably the single biggest reason why code doesn’t get tested.

If you were able to make yourself write your tests first, you would be much more likely to write test for everything you wrote.

This doesn’t help you though if you’ve been tasked with writing tests for all pre-existing code. Yours on someone else’s. In this case, the best help I can give you is to recommend the book “Working Effectively With Legacy Code” where Michael Feathers illustrates how to handle a lot of the common scenarios he has run into with various languages and how to untangle the mess so that it can be tested. I will admit it is a tedious read, but there really is no better resource on the topic.

Lack of Experience

The final reason you might want to think that 100% code coverage is impossible is that you simply don’t have enough experience.

As I mentioned above, my own experience has been that the more I practice TDD, the easier it gets. When I started out, I struggled to write test at all. Then I got to a point where I would at least attempt to write tests after I’d written some code. I’m now at the point where I’m writing tests as I code. Soon, I hope to achieve the ultimate goal of writing test prior to writing the real code. But even though I wasn’t writing the tests first, I can still say that the tests were driving my development because I knew at some point, I was going to have to test the code with unit tests.

But as I’ve monitored the noise on the Internet about using TDD or not. As people have discussed how much of their code should be tested. I wonder, “Just how long has this person been trying to tests?” Along with that, I wonder, “Do they even want to test?” My dad used to say, “It is amazing how much I don’t understand when it doesn’t fit my plan.” Let’s face it, for most programmers, writing tests is not nearly as much fun as writing the application. If this is true, then aren’t you already biased against writing tests for your application? Wouldn’t you much rather write the app and toss it over the fence for someone else to tests? I know I would.

Now combine that with the fact that testing is hard, and you have a recipe for excusing yourself from testing as much of your code as possible.

But, if you stick with it. If you make writing bug free code a personal challenge, you will find that the rewards are worth it.

What would it be like to be THE developer who was always working on new features because no one could find bugs in the features you programmed in the past? What would that do for your career?

The 100% Code Coverage Payoff

I want to conclude with another story that illustrates how writing tests paid off.

I’ve been working on a resource scheduling component for the last several weeks. The bulk of the logic is that if two resources are scheduled for the same time, I need to be able to display that there is a conflict. It sounds pretty straight forward until you look at all the various ways items can overlap. I’ve isolated the logic for this into a class that is quite testable and I had created a test suite with about 400 tests when I was told that along with that requirement, there were a particular set of conditions where what looked like a conflict wasn’t really a conflict. I needed to show that there was an overlap, but I need to display it in such a way as to indicate that it isn’t a conflict.

As I sat down to add in the new logic, I realized that the path I had been going down wasn’t going to work well given this new scenario. What I really needed to do is to do some major refactoring. In fact, you might even say I had to rewrite most of the code I had in place. Now, in the past, I would have been afraid to tear up all that I had done and start over because it would have meant I would have to retest all that I had already worked on … manually! But, since I already had tests in place, I was able to 1) commit what I had done so far to version control so I could get it back if I needed and 2) rip up what I had done, rewrite and refactor so that it would work well with the new requirement and 3) retest with the tests I ALREADY had in place. I’ve added another 100 tests for the new scenarios and I’m pretty confident that the code I’ve written does what it should and doesn’t do what it shouldn’t.

And that whole refactoring exercise took less than 7 hours.

Oh. And I have 100% code coverage!