Last week I proposed a structure for unit test that follows the pre-condition, action, post-condition workflow. Basically what you would see in a Use Case document.

The result of this structure when applied to a general NUnit class is that we will end up with our pre-condition and action in our setup method and our post-condition asserts in our test methods.

The problem with this is that sometimes this doesn’t always fit what we are trying to do.

For example, I’ve been writing selenium test to test web applications I am working on. Each page I am testing is essentially a form that computes a result at the bottom. If I were a purest, I would put the page load object and the setup of the state of the page in the setup method. One for each permutation. And the assert to verify that it computed correctly.

In this case, however, I vary slightly because what I really want is all of these similar test together where I can see them.

But I still keep my code clean by using a TestCaseSource.

What we are going to do is move just about everything into the TestCaseSource. The code that is common between each TestCaseSource is going to still go in the SetUp method, but everything else will be declared in the TestCaseSource.

The basics of how TestCaseSource works is that we setup a Property or a member variable that returns an IEnumerable. By using the built in TestCaseData class we get a lot of control over what displays. I’m not going to go over that here. I’m sure you can read the documentation as well as I can.

But what you may not realize when you first look that this documentation is that we can pass in functions and not just objects. This gives us quite a bit of freedom in what we do here.

So by setting up our Test method to look like this:

1 | [] |

What we are doing is saying that we expect to find a property or member variable called “DataSource” that will pass us a function, a list of functions, and another function.

The test body runs the first function to do any pre-condition work. Then it loops through all of the function in the actions list to get the code to the state we need it to be in and then we finally call the assert to test our code.

Here is a sample of what our DataSource property looks like:

1 | public IEnumerable DataSource |

I’ve broken out the lambda expressions individually so that you can better see what I’m doing. But in real life, your code will probably look more like this:

1 | public IEnumerable DataSource |

You will need the (Action) cast to make the compiler understand what you are trying to do. It isn’t smart enough to know that a lambda express is an Action which is a delegate that take no parameters and returns void.

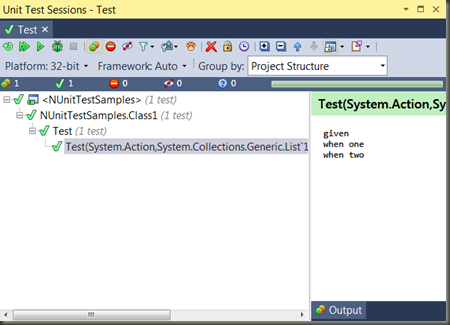

When you run the code, above, we get this output:

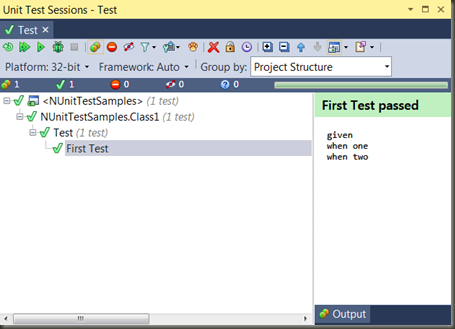

By chaining on the SetName() call, you can make each iteration show up as it’s own unique test so you can see what is occuring in your test runner.

1 | public IEnumerable DataSource |

And this looks like this in the test runner:

Once again, I have to reiterate, this is not something I would do a lot of, but it is a pretty neat trick when you need it.